Very big data

Warning: this area of the website is strictly for the curious.

If you’ve already read The Biggest Footprint, you may want to know more about where all the brain-bending facts in the book came from. This is where we’ve collected many of our data sources.

It’s also where we’ll add any new data that we either hadn’t found or didn’t exist when the book first came out. And where we’ll catalogue any corrections (see ‘The penguin problem’).

Before we get into the details, now would be a good time for a quick primer on Smoosh Theory. We didn’t want to put any equations in the book, but there is going to be one a bit further down this webpage. Don’t worry – it’s a simple, non-threatening sort of equation and you can always scroll rapidly past it if you get frightened.

Smoosh theory 101

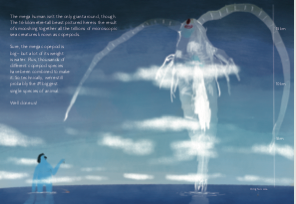

Early in the book, you may remember we met a tribe of plasticine people. The tribe has a population of eight, so when we smoosh them together we get a plasticine giant, who we’ll call Megamorph. The mighty Megamorph weighs eight times more than an average plasticine person.

So far so straightforward – Megamorph is made up of eight times as much plasticine, so naturally they are eight times heavier.

But what about Megamorph’s height? They won’t be eight times taller; there’s not nearly enough plasticine for that. You’d end up with a stretched out string of plasticine. If we keep the proportions the same, it turns out there’s only enough plasticine to make Megamorph exactly twice as tall as one of the original tribespeople.

That’s because of the following equation (we’ll put animals around it to make it less scary).

This equation, where n is the number of things being smooshed, is what we call the Grand Smooshing Theorem. What it means is that if you put n things of the same kind into the Smooshing Machine, what comes out will be taller than what you put in by a factor equal to the cube root of n.

It’s a mathematical way of expressing the fact that all the stuff you are smooshing together needs to be spread out across three different dimensions, length, height and width.

So a tribe of eight people will smoosh together to become taller by a factor of ∛8=2.

And if you do the same thing with a tribe of 7.8 billion (that’s our global human tribe), you’ll get a giant who’s taller by a factor of ∛7,800,000,000 ≈ 1,983.

All of which explains why the mega human – at about 3km tall without shoes on – is about 2,000 times taller than a typical person even though we’re about 8 billion times more massive.

(For more on the theory, you could try this GCSE maths video. As for why the mega human is such a vivid shade of blue, that may forever be a mystery.)

A smorgasbord of data

To work out the sizes of all the smooshed animals and objects in the book, we needed a tremendous amount of data to feed into the Grand Smooshing Theorem. This ranged from the worldwide giraffe population to the number of pet cats we own, from the number of avocados we grow, to the area of new real estate we build.

These data points come from scientists and experts but nonetheless they are estimates and should not be depended on in life-or-death situations. Where possible, we have used internationally reputable sources such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature or the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations.

If you’re curious to dive under the surface of The Biggest Footprint, read on!

Authors’ notes

Pages 2&3

The world’s population likely reached 7.8 billion in 2020 according to the UN. For a live view of how quickly this number is ticking up as new babies are being shot screaming into the world, check out the population clock at Worldometer.

Pages 4&5

The claim that it would take a thousand years to greet the population of earth one by one is based on spending about 4 seconds with each person, which doesn’t allow for chatting with anyone you like the look of. No using the loo or sleeping either. Eugh.

Pages 6&7

Lots of people have done the simple calculations to figure out how much room the human race would occupy if we were crammed together more closely. The Wait But Why blog worked out that, if we all lived as densely as people do in the Manhattan borough of New York City, we could all fit comfortably in New Zealand.

But could we all fit in Greater London, as this blog on crowd sizes suggests? Based on the London Assembly’s figure of 1,572 kilometres squared for the area of London, yes we could.

We’d have to stand pretty close together though – about five people to a square metre. You can try this with friends – it’s a squeeze, but do-able!

Page 14&15

To work out the size of the mega human, we needed to know the size of the average person being smooshed.

According to the global health scientist network NCD RisC (via Worldometer), the average adult woman is 159.5 cm tall and the average man is 171 cm tall. Based on these figures, the mega human would be nearly 3.3km tall. Factoring in the presence of kids in the population brings the average height down a bit, hence our figure of about 3km.

The mega human’s total weight of 390 million tonnes was worked out based on an average human weight of 50kg – an approximation sometimes used by scientists for the average weight of a human in a population including children.

We also worked out that the mega human’s weight increases by 130kg every second, a particularly eye popping stat. Just picture new human flesh equal to the mass of five Dwayne the Rock Johnsons being generated in about the time it took you to read this sentence! (This rate of growth is a gross approximation based on the human race steadily increasing in numbers to hit the UN’s 2050 population predictions. It includes no adjustments for changing demographics, such as changes in the proportion of children in the overall population, or rising obesity rates.)

Pages 16&17

You can calculate the widths and lengths of the mega human’s various anatomical bits by simply multiplying the average human’s dimensions by 1,983 (see the introduction to this page for why).

The average eyeball is 2.24cm across and the overall eye structure is larger, so you could expect the mega eye to measure up to 70m, a typical size for a park soccer pitch. You have to imagine that the vast iris would be hypnotically beautiful for spectators, if a little offputting.

Most people can fit a swab 3cm up their nose if required, meaning the mega human’s nostril forms a cave at least 60 metres deep. That’s spacious enough to comfortably accommodate all 52 metres of Nelson’s Column, although putting things up your nose is not advisable, particularly a large granite monument covered in pigeon poo.

Pages 18&19

A running route following the equator all the way around is 40,075km – a multi-day journey even by plane.

For the mega human, though, assuming our performance scales in proportion with our long limbs*, this would be the equivalent of an afternoon’s run. Depending on our fitness levels, we estimate it could be completed in three hours flat, with each of our strides measuring over a kilometre and each footfall creating a seismic event of about Richter scale 7. (This is another approximation, modelled on the energy released when a 390-million tonne object falls from 500 metres: 1.95x10^15J).

* Actually, there are lots of real-world reasons why extreme size could make it hard for a giant human to run properly (or indeed for giant animals to exist at all). Our scaled-up muscles might struggle to create the needed explosive strength; our enlarged bones might snap under the pressure of our huge weight; our long nerves might slow down our reactions and cause us to overbalance or trip. However we choose to believe that in the world of our book, if Professor McCrackers can build a Smooshing Machine and persuade everyone on earth to jump in, she can develop a smooshing process that overcomes these challenges!

Pages 18&19

This oceanic scene shows the mega human with an average sized humpback whale (12-16m long) and the Titanic, 269m long, for scale (of course the real Titanic is at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean; the one in the picture is a lifesize replica built especially).

With an average depth of 450m, the Red Sea makes an ideal bath for the mega human – just as long as we’re careful not to sit on one of the scorchingly hot hydrothermal vents known as Black Smokers, which could give us a nasty burn.

Pages 20&21

One of the mega human’s hairs would be around 20cm in diameter and would need both hands to grasp, like an extremely thick rope (based on the average human hair width being 80,000-100,000 nanometres). You’d need a lot of shampoo just to get one strand looking lustrous.

Page 22&23

We didn’t want to include the mega bodily functions in the book in case of grossing out sensitive readers, but inquisitive minds insisted.

A healthy normal urine volume is 250 to 500ml per wee, so the mega human could – in a single trip to the loo – produce a couple of million cubic metres of urine. That’s about the same volume as all the canals of Venice (which we calculate as 2.15 million cubic metres based on data sourced from a webpage of Venipedia.org that appears to no longer be online).

(Weeing in Venice’s Grand Canal, whatever your size, is of course an act of vandalism against one of the most beautiful places in the world and is strongly discouraged.)

Page 23

The mega brain, made of all our regular brains, is responsible for initiating everything humans do including starting wars, chopping down forests and filling the skies with smog.

On the other hand, a thinking organ this size has the potential to do amazing and as yet unimagined things – if we could only get it hooked up properly.

A 2004 study showed the average brain weighs 1.28kg, with a front-to-back measurement of 17cm. The mega brain would weigh in at around ten million tonnes and measure 330m front to back. With custom heavy duty cranes, you might be able to load it onto three of the world’s largest cargo ships, though you’d exceed their maximum carrying capacity by a factor of ten and almost certainly sink or capsize them in the process!

Whether you are thinking about what to have for lunch or solving differential equations, your brain is said to use about 20% of the calories you consume each day – 260kcal a day according to Scientific American. That lets us estimate the total amount of energy used by all human brains: on these numbers, it’s the equivalent of the energy produced from burning 74 million tonnes of oil a year (a unit sometimes referred to as Mtoe).

To put it another way, the entirety of human thought requires about the same amount of energy as it takes to power the homes and industries of the small nation of the Netherlands (72 Mtoe in 2019).

Pages 24&25

Now we’ve seen how big the mega human is, what about other animals? This page shows the mega tiger at around 44m long, based on a WWF population estimate of 3,890 wild tigers and a typical tiger length of 278.5cm (averaged over males and females). We can also figure out the mega tiger’s canine teeth will be over a metre long, and its vertical leap might be as high as 78m.

This big cat would truly be a giant, towering over three-storey houses… yet still minuscule in comparison to the mega human.

Note that the WWF’s population estimate only includes adult and ‘sub-adult’ tigers (meaning older than a year). For this reason we have not attempted to make a downward size adjustment for the presence of cubs in the population. (Many wildlife population estimates are based on adult specimens only, and in general our smooshed animal size estimates are based on adult size data only.)

Pages 26&27

The mega giraffe would be 230m tall (that’s based on an estimated population of 97,500 and an average mature height of 4.3-5.7m). That makes it about as high as one of the mega human’s ankles.

Page 28&29

Sumatran rhino are the smallest rhinos on earth, and there are believed to be less than 80 left, making the mega Sumatran rhino the size of a double decker bus.

Meanwhile only two Northern white rhino remain. Named Najin and Fatu, both are females, meaning that, sadly, the species will soon be extinct. The pair smoosh together to form a mega white rhino 4.4m long.

The world has around 3,500 great white shark (Stanford study via Wikipedia). Based on their average adult size, they would smoosh together to form a mega great white shark 64 metres long.

That’s big enough to swallow a yacht whole and cause even the mayor of Amity to shut down the beaches, but still just a nipper from the mega human’s point of view.

Pages 30&31

Copepod are found in water everywhere. Trail a bucket through any sea, lake or river and under the microscope you will likely find a bunch of these tiny crustaceans darting and sculling around in the water.

The 16km mega copepod is based on a crustacean expert’s rough estimate that there may be 1.3x10^21 copepods (that’s a 13 with 20 zeroes after it), which are typically 1-2mm in size. There are a LOT of different copepod species, however, and a lot of variation in size and various larval forms before they reach adulthood. Nonetheless it seems likely that smooshed together, they would indeed dwarf the mega human.

It’s unclear if any one wild species can match the mega human in biomass terms, but a potential rival is the mighty Antarctic krill, whose biomass in summer is estimated at 379 million tonnes (compare our estimate for the human race’s weight of 390 million tonnes).

Pages 32&33

Here’s a whole bunch of smooshed animals having a party. Let’s see who’s on the guest list (note that where sources give population estimates as ranges, in the book we have quoted the midpoint for brevity):

The mega springbok, 176m long (smooshed from a population of 2-2.5 million, according to the entry by JD Skinner in The Mammals of Africa (ed Kingdon and Hoffmann), though estimates vary; average size 1.2-1.5m)

The mega giraffe, 230m tall (see p27 notes for sources)

The mega honeybee, 188m long (smooshed from an estimated 2 trillion honeybees in beekeeper controlled hives; average size 15mm)

The mega emperor penguin, 98m tall (smooshed from a population of between 531,000 and 557,000; average size 1.2m). *Please note that captions in the first print run of The Biggest Footprint wrongly listed the number of emperor penguins as 410 million on p32, 64 and 95 (see The penguin problem). We apologise to all readers and penguins for this copy-and-pasting error. It does not affect the illustrations, which were correctly calculated based on the midpoint population estimate of 544,000. The mistake will be fixed in subsequent print runs and in translated editions.*

The mega African elephant, 242m at the shoulder (smooshed from a population of about 415,000; average size from 2.5 to 4 metres from shoulder to toe)

The mega giant panda, 19m long (smooshed from a wild population of 1,864; average size from nose to rump 1.5m)

The mega tiger, 44m long (see p24 notes for sources)

The mega monarch butterfly, 60m wingspan (smooshed from a population of 250 million; average wingspan 8.9-10.2cm according to The Urban Naturalist by Steven Garber)

The mega house sparrow, 165m long (smooshed from a population of 896m-1.31m, average length 14-18cm according to The Sparrows by Denis Summers-Smith)

The mega pygmy three-toed sloth, 5m tall (smooshed from a population of 500-1,500; average size 50cm)

The mega koala, 55m tall (smooshed from a population of 329,000; average size 70-90cm)

The mega polar bear, 72m long (smooshed from a population of 29,000 to 31,000; average size 1.8-2.4m (female), 2.4-3m (male), according to The Polar Bear by Annie Hemstock)

The mega rock dove or common pigeon, 220m long (smooshed from a population of 260 million; average size 32-37cm)

The mega ring-tailed lemur, 6m long (smooshed from a population of 2,000 to 2,400; average size 45cm not including tail)

Page 34&35

Population figures are almost always estimates, but trying to establish, say, the population of African elephants a hundred or two hundred years ago introduces even more uncertainty. Still, the trend of the numbers we found is not in doubt. It tells a sad story of falling populations and shrinking ‘memories’ (a term for groups of elephants).

African elephants are thought to have gone from over 26 million in 1800, to 5 million in the twentieth century, to 415,000 in 2016… while the human race has grown from around 1 billion in 1800 to 2.58 billion in 1950 to nearly 8 billion today.

Page 36&37

We were also able to find historic data on enough marine species to paint a picture of the smooshed seas a century ago compared to today. The following species are depicted:

Caribbean monk seal (population in 1836 was 500; by 1950 there were none; average size 2.4m)

Blue whale (population before 20th century commercial whaling was between 200,000 and 300,000; today there are between 5,000 and 15,000; average size 82 to 105m)

Southern right whale (population before 20th century commercial whaling was between 70,000 and 100,000; today there are 14,000; they grow to 15m)

Pacific bluefin tuna (biomass is 13,795 tonnes, 2.6% of the projected 1900 total; they are about 1.5m long and weigh 60kg)

African penguin (population in the 1900s was 1.5 million to 3 million; now there are 23,000; they are about 45cm long)

Pages 38&39

The vast majority of wild species populations haven’t been doing well lately, but what about the animals we farm?

Here we have a different story. In fact, they have grown to become the biggest mega creatures on the planet. The mass of cows alone is greater than that even of humans. (We’re lucky they’ve showed no signs so far of staging a revolution.)

An influential paper called The Biomass Distribution on Earth, which we referred to a lot while writing The Biggest Footprint, says that domesticated poultry (mainly chickens) weigh three times more than all other wild birds combined. That’s a pretty powerful proof of how much the mega human’s activities are affecting which species thrive and which decline.

Shown in this gathering of fast-growing species are the following mega creatures:

The mega chicken (smooshed from 23.7 billion chickens; average 40cm tall)

The mega cow (smooshed from 1.4 billion cows; an average Holstein is 600kg and 1.47m tall. Each produces between 70 and 120kg of methane per year, which between all 1.4 billion cows amounts to a significant quantity of greenhouse gases.)

The mega pig (smooshed from pigs weighing about 137 billion tonnes; a domestic pig's head-plus-body length ranges from 0.9 to 1.8m, and adult pigs typically weigh between 50 and 350 kg [from a Wikipedia contribution by Dr Christopher Sherwin, Senior Research Fellow at Bristol Veterinary School])

The mega virus (smooshed from a possible ten trillion quadrillion virus particles across all virus species, most of which measure between 10 and 200 nanometres. The mega virus is not to be confused with Megavirus, a specific kind of virus recently discovered in ocean waters off the coast of Chile. At 680 nanometres it’s particularly large, but only in comparison to other viruses.)

Page 40&41

Noodles the mega dog, the mega human’s best mega friend, stands over half a kilometre tall at the shoulder and is smooshed from an estimated 900 million pet and stray dogs worldwide (from Free Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation, ed Matthew Gomper, referenced on Wikipedia; the average golden retriever is 27 to 37kg and stands 51-61cm tall at the shoulder).

As these dogs include every breed and every possible mix of breeds, it’s fair to say that Noodles is the ultimate mutt.

Pages 44&45

Here we have a picnic showing how much of some of humankind’s favourite food items we eat in a year. To create this feast we relied on data from the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations, whose FAOSTAT website is a kind of all-knowing world brain that can answer any question you may have about farming, food security and nutrition.

(Individual data points on FAOSTAT are not linkable so you may need to enter your own searches on FAOSTAT to find some of the data below. Most recent data at time of print was for 2018, 2019 figures are now available.)

In the picture you will see:

The mega rice bowl, 3km across (782 million tonnes were produced per year in 2018)

The mega, 840-billion litre carton of milk, 2km tall (843 million tonnes of milk were produced per year in 2018; a litre of milk weighs approximately one kilo)

The mega, 29-billion litre bottle of wine, about 1km tall (29 million tonnes of wine were produced per year in 2018; a litre of wine weighs approximately one kilo)

The mega sack of wheat (771 million tonnes produced yearly as of 2018; its density is 769kg per cubic metre)

The mega maize or corn cob, 3km long (1.15 billion tonnes produced yearly; a typical cob is 13.5cm long and weighs 80g)

The mega egg, 650m tall (83 million tonnes of eggs produced yearly; a typical egg is 6cm long and weighs 64g)

The mega avocado, 450m tall (6.4 million tonnes of avocados are produced yearly; a typical avocado is 13.5cm tall and weighs 170g)

The mega can of spam, 60m tall (44,000 cans produced an hour; a standard can of spam is 8.25cm wide and 9.9cm high)

The mega bottle of palm oil, 1.2km tall (71 million tonnes produced a year; density 0.91kg per litre)

The mega lollipop, 2.1km wide (based on global sugar cane production of 1.9 billion tonnes a year; and a typical spiral lollipop made of pure sugar measuring 6.5cm across and 50g)

The mega tomato, approximately 800m across (based on a figure of 160 million tonnes quoted in text of this article from a global tomato conference; since publication we have found an FAO estimate of 181 million tonnes for 2019)

The mega chicken, 980m long (69 billion chicken are raised per year as of 2018; a typical roasting chicken could be 24cm long)

The mega grass carp, 963m long (this was based on a World Atlas figure of 5,028,661 tonnes production per year; we have found what seems to be a more recent figure since publication of 6,068,014 tonnes per year, though this still refers to 2016. Information on carp harvests are conflicting, with some sources claiming grass carp are the world’s most farmed fish and others that the grass carp comes in second behind silver carp. Anyway, the point stands that we farm an amount of carp that may be surprising to some!)

Pages 46&47

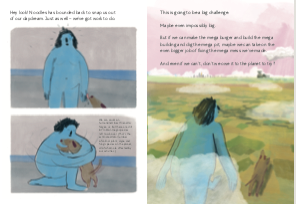

The mega burger recipe is a demonstration of the amount of resources it takes to produce meat.

Just under 80% of the world’s population eats animals (figures from 2010). And not only do most of us eat animals (327 million tonnes of them a year), the animals that we eat, also have to eat – and, over the course of their lives, they have to eat a lot more than their bodyweights. They eat plants such as grass via grazing and also food grown specially for them, often served up in concentrated form in troughs so they can reach a supersized state quickly.

One third of the world’s 4.62 billion acres of cropland is used to make animal feed, a gigantic amount of land equivalent to the area of Europe (not including Russia). All that growing is part of why meat production diverts such a lot of water – between 5,000 and 20,000 litres per kilo of meat. If you ever find yourself eating a quarter pounder, consider that about 13 bathtubs’ worth of water were involved in producing it.

Pages 48&49

The mega burger that results from all this labour, which we’ve modelled on the proportions and density of this little burger here, would be around 1.7km across. (It’s made of all types of meat, not just beef.)

A lot of the food the mega human goes to such efforts to produce and prepare goes to waste, either because of the difficulty of harvesting, storing it and getting it to the people who need or want it, or because we just don’t get round to eating it before it goes mouldy in the fridge. We waste about 1.3 billion tonnes of food a year, enough to make a mountain 2 miles across and 8,000 feet high (we’ve used the Guardian’s calculations; in metric measurements, the food waste mountain is 3.2km across and 2.4km high).

Many of us don’t even consider the hard work that goes into growing and producing our food. You can be sure we wouldn’t waste so much if we were the ones who’d sweated to produce it.

Pages 50&51

Of course many humans are aware of our wastefulness and impact on the environment, and are trying to help in ways that do register on the ‘mega’ scale – at least a bit.

Pea protein production has gone up to 350,000 tonnes a year because it’s a major ingredient in meat alternatives, which we’re eating a lot more of. With that much pea protein, you could create a Greggs vegan sausage roll 430m long.

We’re also beginning the transition to electric cars, albeit gradually; as of 2019 there were 4.79 million and that number will undoubtedly be higher today.

And for a third example, we’re recycling more plastic waste (around 19.5% of what we create). When crushed and compacted the plastic that goes to recycling could fill a compactor lorry similar to this one, but scaled up to 1.8km in length.

Small though these wins may be, they show the mega human has the potential to change its wasteful ways.

Page 54&55

At this point in the book, the mega human goes into a digging frenzy. The first substance we dig is among the most valuable: gold.

There are several reasons why gold has been the most prized of precious metals for so long. One of them is its rarity. According to the World Gold Council, the total gold ever mined amounts to just 190,000 tonnes. Another way of thinking about it is that, if all the gold in all the jewellery and gilt frames and electronic devices and safeboxes around the world could be collected in one place, you could pile it into a gleaming mound just 24m high (that’s based on a conical hill and the density of solid gold being 19.32g/cm3).

Mountain ranges have been excavated and wars fought over that shiny hillock, which is worth about five times more than Amazon.com, Inc.

Diamonds are even scarcer than gold (at least the ones accessible to humans). The chairman of the Diamond Producers Association says all the diamonds ever mined would fit in a double decker bus. (There’s an idea for a heist movie there...)

Tantalum is one of several rare minerals in demand due to their chemical properties (in the case of tantalum, its corrosion resistance).

Tantalum is used in electronic circuits in phones and other devices. Around 1,800 tonnes of it are produced a year, the equivalent of a 4.7m cube of the stuff (that’s based on its density of 16,650kg/m3). That’s enough to help create the capacitors for the mega smartphone, smooshed from an estimated 3.8 billion smartphones worldwide.

Tantalum and niobium, another rare metal, are found combined in the form of ‘coltan’. Wildlife organisations are concerned about the ecological impact of coltan mines in central Africa. (The pictured mega western lowland gorilla is smooshed from an estimated gorilla population of up to 100,000; they grow to between 4 and 5.5 feet tall)

Pages 56&57

A mundane resource the mega human digs up in far greater quantities than gold or coltan is sand and gravel. Our yearly diggings of 32 to 50 billion tonnes a year would smoosh to form a pile around 3km high (based on a loose sand density of 1,442kg/m3).

A lot of this sand and gravel (also referred to as aggregate) is used for building, in particular making cement and concrete. And these days we do make a staggering amount of it. Ten billion tonnes of concrete a year – that’s more than a tonne per human.

Amazingly China alone, between 2011 and 2013, made more cement than was used by the USA in the entire twentieth century, and that’s the stretch when the big American metropolises were shooting up.

To try and bring home the amount of building the world is currently doing, we calculated the size of a mega building containing the equivalent square meterage being created across all new buildings worldwide in a year. According to the UN Global Alliance for Building and Construction report, we’ll add about 230 billion square metres of new floorspace over the next forty years. That averages to 5.75 billion square metres a year if we build steadily.

Smooshing all that space into a single building is an architectural challenge for sure but we think we’ve found a way. The mega building is modelled on the Willis Tower in Chicago, with a floor every 4 metres – but instead of 110 floors our version has ten thousand. And instead of being 70 metres wide, ours has a square footprint of around 800m a side. With a building this tall we thought it best to use some of the world’s fastest elevators, which travel at an ear-popping 60km/hour.

Just next to the mega building, for scale, you may be able to see a couple of comparatively tiny shapes – the world’s largest and tallest buildings respectively (the largest by floor area is the New Century Global Complex in Chengdu, China, and the tallest is the Burj Khalifa in Dubai).

Our claim about having enough concrete left over after building the mega building to patio an area the size of Croatia is based on using a rather thin layer of concrete that admittedly might not weather too well.

In that vast grey concreted expanse, you can also see, parked up, the 5km-long mega car (smooshed from 1.3 billion cars of all fuel types) and the 2km-long mega plane (smooshed from the 25,900 aircraft in the world’s commercial fleets).

Pages 58&59

Now we come to the Big One, or rather the Big Three: oil, coal and gas, the fossil fuels. Digging up (or pumping up) this dark triad and then burning them is an unhealthy addiction for the mega human.

The 2.8km high oil barrel is based on the proportions of a standard barrel and a recent annual global oil consumption estimate made by BP (36.4 billion barrels of oil). The 3km coal mountain is based on the International Energy Agency’s figure of 5,515 megatonnes of coal produced per year, a number that has been going up internationally even as some countries have phased coal out. And the figure of 4,000 billion cubic metres of gas also comes from the IEA.

We suspect the air in this extremely smoky smooshed scenario would quickly asphyxiate and kill a normal human (breathing poor quality air over time, even with lower concentrations of pollution than shown here, is believed to kill 8.7 million people a year).

The quantity of CO2 released by fossil fuels each year is around 35 billion tonnes. It’s hard to understate its impact.

For a clear numbers-driven account of the science of climate change, try The Temperature of the Earth, an ebook by physicist Malcolm McGeoch.

Pages 60&61

This spread sums up our combined digging activities. It shows a mega pit equivalent in volume to all the 90 billion tonnes of matter we extract from the earth each year. Based on the density of dry soil and gravel, we’ve visualised it as a pit sixty cubic kilometres in volume.

If you’ve ever known a dog who likes to dig you’ll know it can be a compulsive habit. In the case of the mega human, it’s possible that in the back of our mega mind, we know full well that our mania for mining and taking has gone too far. We just don’t seem to have been able to do anything about it yet.

Pages 62&63

Sorry to pile on the bad news but our chopping habit is also out of control. The amount of wood we ‘produce’ per year is 5.5 billion cubic metres according to the FAO, roughly equivalent in volume to the trunk of a 35km-high tree, 2.5km around the base. It’s also been calculated that our yearly chopping does for 15 billion trees a year. That’s about two each. Imagine your two trees, maybe in your neighbourhood, maybe further afield, perhaps young, perhaps old and gnarled, and all the wildlife they support, and all the air they clean…

Some of the creatures displaced by felling in rainforests include the 37m-tall mega cassowary (smooshed from a population between 10,000 and 20,000; each 1.5 to 1.8m tall), the 59m-tall mega orangutan (smooshed from a population of 104,000; an average of 126cm tall), and the 11m-tall mega great green macaw (smooshed from a population of between 1,000 and 2,499; each 85 to 90cm tall according to the Handbook of Avian Body Masses, ed John B Dunning).

Pages 64&65

The list of mega-human-caused problems unfortunately goes on – when you live as large as we do, you end up causing all sorts of unforeseen calamities. It’s thought, for example, that every year, another 8 million tonnes of plastic find their way into the oceans, where they can poison, strangle or trap seabirds, turtles, whales and fish.

That’s the equivalent of a kilo of plastic getting into the sea for every human – in weight terms equal to over 100 average PET bottles (which weigh only 9.9g each on average). In reality, of course, the plastics in the sea aren’t just domestic waste but also include large amounts of commercial plastic and discarded plastic fishing equipment.

The quantity of clothing we produce is also creating XXXL-sized problems, due to the extremely resource-intensive nature of textile production and the rate at which we throw old clothes away. Some of the synthetic fabrics popular used by ‘throwaway fashion’ brands will be around in the ecosystem, leaching dyes into the water, for centuries to come.

And then there’s the mega human’s love for exotic animal products and pets. The WWF says 20,000 African elephants are still killed every year for their tusks even though all international trade in ivory was outlawed in 1989. The smooshed tusk shown in the illustration is 70m long, based on an average 2m tusk. Surely it should be too big to turn a blind eye to?

The armadillo-like creature larger than a 747 is the mega pangolin, smooshed from all the 30-100cm long pangolins illegally poached every year – as many as 2.7 million according to some sources. Their meat is sold in restaurants and their scales in medicine shops, especially in China and Vietnam. Again, all such trade is illegal but still happening on an industrial scale.

Finally the caged mega songbird on the left is formed from all the 1.5 million live birds traded illicitly every year to be sold as pets.

Practically all the megahuman-caused problems mentioned so far in the book contribute to biodiversity loss. They destroy rare species’ habitats and interfere with their normal life cycles. The consequences can be seen in the decline of most wild populations on earth like the duck-billed platypus (in its smooshed form, around 26m long based on a population between 30,000 and 300,000 and an average size of 48.75cm).

Many species are heading for extinction, like vaquita porpoise (14 left) and the Hainan black crested gibbon (28 left). And others are tragically already gone for good.

The shrinking elephant on p35 and the lonely ocean on p36-37? All a result of the mega human’s array of big bad habits.

Pages 66&67

Isn’t it typical to get sick just when you’ve already got lots going on? A mega virus is entering our cavernous airways. This time it’s not all virus species smooshed into one, but a single species with a shape that may be familiar to everyone…

Mathematician Christian Yates has calculated that all the Covid-19 particles in the world (as of February 2021) would number as many as the grains of sand in the world. He also calculates that, despite this tremendous number, if they were separated into a pure form, they would easily fit inside a fizzy drinks can.

Pages 68&69

A poem from the 1970s apparently once included the lines, “…there are now more of us alive than ever have been dead. I don’t know what this means, but it can’t be good,” and perhaps this was the start of the untrue rumour that the living outnumber the dead.

According to Carl Haub of the Population Reference Bureau, it’s the other way around. He estimated that the number of people who’ve ever lived is over 108 billion, meaning around 100 billion have died. These smoosh to form the mega ghost, who’s 12 times more massive than the mega human and 2.3 times taller. Scary! But a reminder that, large as humankind is right now, our present population is still just one chapter in the historical epic that is the human story.

UPDATE: Since The Biggest Footprint was first sent to print the Population Reference Bureau has revised its estimate of people who’ve ever been born up to 117 billion. The mega ghost is growing.

It is hard to know how the mega ghost would feel towards its mega descendant. It can’t really claim the moral high ground over us given its track record of war, genocide and slavery. But we can’t help feeling it would be a bit disappointed by the escalating troubles our generation has created for itself.

Pages 70&71

The research of a team at the Weizmann Institute of Science was one of the reasons we wanted to write The Biggest Footprint. The team, led by Professor Milo, say they love to ‘understand and explain the world using numbers as [their] sixth sense’. Their influential paper, The Biomass Distribution on Earth, quantifies and compares all known life.

It features several startling conclusions, such as what a tiny fraction of life mammals and birds are of the whole, despite their hold on our imaginations and sympathies; or the weight of biological kingdoms we do not usually give much thought to such as the fungi and protists; or the sheer dominance of plants, which make up 80% of global biomass.

The place of humans in the big picture is what really stands out though. We represent just 0.01% of total biomass, what could almost be a rounding error in the accounting books of life.

ALOE, the fantastical creature we’ve created to represent All Life On Earth, is a fusion of the different biological domains and utterly dwarfs the mega human.

Pages 72&73

A follow-up paper from Professor Milo’s team came to another incredible conclusion: that all the stuff humans have made (not including what we throw away) is heavier than all living things combined.

To show this, we’ve smooshed all our possessions (from tarmac and buildings and bridges to oil tankers, picnic benches and pepper shakers) into a vast ball of junk. To find out how big the ball of junk is we had to make a few slightly arbitrary but not unreasonable assumptions about its density (we had to do the same with ALOE on the previous spread). With these assumptions in place we made both to be approximately 70km tall.

Meanwhile the mega human is only just visible as a blue speck at the bottom left.

This illustration is a testament to the fact that, even though our species is not huge compared to the rest of nature, we churn out an utterly disproportionate amount of stuff. That’s part of what it means to be living through the Anthropocene, an era where the activities of humans are a primary force, or even the primary force, influencing the earth and the climate.

While we’re on this page, it’s interesting to imagine an even bigger-picture perspective. ALOE and the mega ball of junk between them fit on only a few hundred square kilometres of ground. You could fit them on an island such as Madagascar and leave the rest of the planet as a derelict expanse of land and water. You could even smoosh all the water on the planet, too, into a sphere 860km across, which would fit easily in the US.

It goes to show that from a certain perspective nature and civilisation (and the water that makes them possible) are just a thin film on the crust of the 40,000km rock we’re clinging to.

Pages 78&79

The mega kakapo (3.6m tall) is smooshed from a population of 208 birds (as per this article; the exact number obviously fluctuates regularly). These fluffy, flightless, ground-running New Zealand birds have suffered from humans encroaching on their habitats and are extremely vulnerable to predators. Concerted efforts have built the population back up from around 50 in the 1990s, with entire breeding populations transported to four predator-free islands off the coast (something we depict the mega human doing on a kindly whim).

The fragile state of the kakapos means they are not out of the woods but we’ve chosen the kakapo rescue project as an example of an ecological good news story that helps wake up the mega human to the difference it can make when its good intentions and actions are coordinated.

Pages 80&81

Forward projections about what our actions will achieve are like plans taking shape in the mega human’s massive brain. Scientists at Yale say that if we’re able to plant a trillion new trees, they could offset a decade of carbon emissions.

Now it’s up to the mega human to act on the plan.

Pages 84&85

Here we can see an idyllic scene anticipating how the mega human’s future might look if we’re able to follow through on plans like the tree-planting one on p81 or this rewilding one mentioned on p83. In this illustration, we appear uncharacteristically calm, so much that various mega animals seem to feel comfortable enough to sit on or near us.

These include:

The mega giraffe (see p27 notes)

The mega grandidieri baobab, 275m tall (smooshed from a population of 1 million; each is 25 to 30m tall)

The mega Canada goose, 160m long (smooshed from a population of 5.1 million averaging 92.5cm long)

The mega elk, 250m long (smooshed from a population of 2 million, 2m from nose to tail)

The mega king eider duck, 57m long (smooshed from a population of 870,000, averaging 60cm long)

The mega Indian peafowl, 50m long (smooshed from a population of 100,000 averaging 107.5cm long according to Pheasants, Partridges and Grouse by Madge and McGowan)

The mega freshwater crocodile, 115m long (smooshed from a population of 100,000 growing between 2 and 3 metres long)

The mega great plains zebra, 130m long (smooshed from a population of 200,000, which average 2.3m long)

The mega Bornean orangutan (see p61 notes)

The mega African elephant (see p32 and 33 notes)

Page 86&87

Noodles the mega dog’s loyalty seems to know no bounds but there are a lot of other species left to win over. It’s been estimated there are 8.7 million species on the planet – and that really is an estimate because the same piece of research estimated that over 80% of these species are as yet unknown to science. Life exists at scales large and small and even when it’s shrinking it retains unfathomable mysteries.

Page 90&91

Following the de-smooshing process, the crowd of eight billion people looks more determined, more purposeful… well, okay, they’re a bit far away to see their individual expressions, but having experienced a collective awakening of planetary proportions, you can imagine that’s how they might be feeling.

Unfortunately due to a possible IT error, no one has de-smooshed a couple of the mega animals – the mega Emperor penguin (see note on p32 and 33), and the mega cat (smooshed from a slightly dated population of 600 million).

Maybe they’ll hang around eating the British fishing industry’s entire catch as a reminder of our shared experience being the mega human.